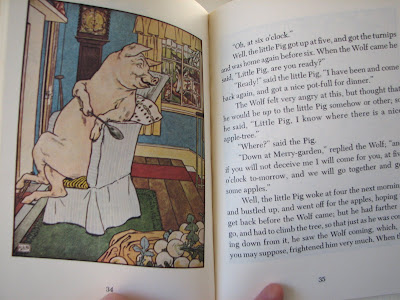

The book above, by the renowned English illustrator L. Leslie Brooke was my first literary love. There's no copyright date in my copy (not too unusual with older books), much less a printing date (also not unusual, even in books printed since 1984), but I'm guessing from the copies I've located online that it was published in the 1920s. It has to have been printed prior to 1958 (when it came into my family's possession) but whenever it was published, it's clearly in the suspect category of pre-1985 books. It's long, long out of print, somewhat rare, but not apparently in the too valuable to be given to a child, as I easily located three copies online today, all for less than $20 (which is less than many new hardcover nursery rhyme collections retail for). (Some of Brooke's books have been preserved by the Gutenberg Project, but this is not one of them.)

The book above, by the renowned English illustrator L. Leslie Brooke was my first literary love. There's no copyright date in my copy (not too unusual with older books), much less a printing date (also not unusual, even in books printed since 1984), but I'm guessing from the copies I've located online that it was published in the 1920s. It has to have been printed prior to 1958 (when it came into my family's possession) but whenever it was published, it's clearly in the suspect category of pre-1985 books. It's long, long out of print, somewhat rare, but not apparently in the too valuable to be given to a child, as I easily located three copies online today, all for less than $20 (which is less than many new hardcover nursery rhyme collections retail for). (Some of Brooke's books have been preserved by the Gutenberg Project, but this is not one of them.)My mother began reading to me as soon as I was born. I enjoyed all the books she shared with me and my older sister, but this book was my hands-down favorite, and the page above, an illustration from the rhyme "Cock-a-Doodle-Doo," was the one I loved best of all. I loved it so much that I "kissed" it (in the big open mouthed slobbery style typical of babies) until it simply dissolved into a pulpy, mushy mess. I was terribly sad when it was gone (though that didn't stop me from loving many other pages in the book to mush), so my kind grandmother Kee gave me this replacement copy for Christmas that year, when I was 15 months old. This copy shows no signs of having been chewed or licked at all and is in remarkably good shape considering that in the years since I have often used it for artistic inspiration/reference, and I also read it to all three of my kids many times when they were babies and toddlers.

Despite my consumption of this evil, almost certainly lead-laced vintage book (look at the bright reds on the rooster), and despite growing up in a generally lead rich environment (I've lived my whole life in older homes, several of which were extensively renovated while I was in them, drank tap water that flowed through lead-soldered pipes, played and gardened in soil undoubtedly contaminated by the leaded gas that was used then, and of course always had my nose buried in those dangerous pre--1985 books), I managed to be accepted to Yale, and even graduate with honors. And then I went onto the University of Virginia where I got an M.Ed. and a Ph.D. in clinical child psychology.

There are several reasons this story is important with regards to CPSIA. First, the way I loved my book with my mouth as well as my eyes is typical of babies. Few babies actually consume pages (especially now that board books are widely available and much sturdier), but most do lick, suck and chew on the cardboard pages. Thus the people who worry about babies' lead exposure are right to be concerned about whether books pose a lead poisoning hazard. And based on my reading and the reactions of many parents when I tell them about the law, parents are scared of books now (and not just the vintage ones). See this article and the comments on Parent Dish and this piece by an Australian pediatrician if you doubt that.

This by no means though indicates that I think the CPSIA position toward vintage books for kids 12 and under is even remotely reasonable. Note that although I devoured my first copy of the book, the second copy is unmouthed, despite many more years of loving. This pattern is actually fairly typical. As this research study indicates, children's "mouthing behavior" peaks between 6 and 15 months and by age 3 years, the licking and chewing of inappropriate objects has dropped to quite low levels . This is why both the U.S. and the EU have special "small parts" rules for toys intended for children below the ages of 36 months; after that, it's reasonable to expect that most typically developing children will have learned not to put unacceptable items in their mouths. (Interesting side note: according to many parents from my own folks' generation, mouthing of books ended at a much age than it does today; because there weren't sturdy board books available, parents taught even little ones to treat books with more care.)

It is thus hard to understand why on earth Congress fought hard to extend the age range under CPSIA to 12, well past the age when mouthing is a concern. The only explanation I've seen is that some consumer groups argued that young children sometimes play with their older siblings' toys; by that argument, though, we ought to limit lead severely in ALL products for any age, since youngsters also get into their parents' things (ever seen a baby chewing on Daddy's keys or sucking Mommy's shirt?) and have frequent exposure to household objects meant for use by the whole family. Yet we're not regulating lead in bathtubs, sofas, kitchen utensils, TV remotes (another favorite of the small fry set), cell phones (saw a baby chewing his grandma's today at Costco), or the family car, which is definitely a lead and phthalate hazard (in the battery, in weights used to balance wheels as well as other metal alloys, with phthalates likely in the vinyl components). By the way, I'm not arguing for an adult version of CPSIA; the economy is tanking well enough on its own and with this law without more onerous provisions to push it over the cliff. I'm just saying.

The question remaining that I haven't answered of course is whether it matters that a baby sucks on a book with lead in the printing inks. I've been combing the internet, trying to track down research about the absorption of lead from ink, and I think it's intriguing that there are no reported cases ever (that I've been able to find) of anyone being harmed by the lead in ink. You'd think the occasional bookworm, printer, or literary-minded toddler would show up with a case of lead poisoning traced back to the printed word (or picture). I did, however, find this old NIH study that examined the pH conditions that caused lead to leach from printed paper; stomach acid pH did cause some leaching, but saliva level pH did not. This finding suggests that babies are likely only at risk if they're consuming the pages (as I did) -- but that ordinary gumming, sucking, and licking is not a problem. Maybe a little parent education to discourage them from letting babies eat paper would be good -- look at the success of educational programs like "Back to Sleep." Not every problem needs a heavy handed law to solve it.

I'm sticking in a few more illustrations by L. Leslie Brooke here, to give you a little break from so much reading in case you're too lead-damage to sit still and pay attention for long. This is another illustration from the same book ("Simple Simon" fishing for a whale in his mother's pail).

The next is the cover of one of Brooke's best known books, also a vintage copy. It at least is available in post 1985 copies, though none is close to as nice in quality as this.

The picture below is one I made in high school as an illustration for a story I wrote for my much younger brother. You may be able to detect the influence of Brooke (and also Beatrix Potter). I was so lucky to have had the outstanding reproductions in my old books, which were printed on a heavy, glossy stock that really brings out the subtle layers of wash and the textures of the brush strokes and pen and ink.

Okay, now for the big finale. It would be just as silly to conclude that eating a lead book caused me to get into Yale (or that it was harmless and irrelevant) as it is for CPSIA to conclude that these old books are so dangerous that they must be kept from everyone under the age of 13. The fact that two things occur together (they are "correlated" in the lingo of science) does not indicate that one caused the other. (Obviously, but for my lead exposure, I'd be another Einstein.)

Okay, now for the big finale. It would be just as silly to conclude that eating a lead book caused me to get into Yale (or that it was harmless and irrelevant) as it is for CPSIA to conclude that these old books are so dangerous that they must be kept from everyone under the age of 13. The fact that two things occur together (they are "correlated" in the lingo of science) does not indicate that one caused the other. (Obviously, but for my lead exposure, I'd be another Einstein.)Just kidding, of course. But it's not silly to hypothesize that there is a cause and effect relationship between wide and frequent exposure to books and school achievement. This correlation has been known since at least the 1920s (and probably suspected by many teachers and parents before then). And that's why it's such a tragedy that CPSIA could lead to the loss of so many books. Aside from the fact that it will reduce the variety of children's books (since most have never been reprinted and never will be), it will also decimate the number of inexpensive or free books available to children. It's easy to find vintage books for as little as a quarter at library or yard sales or thrift shops (or at least it used to be) - try to find a new book available for that. Even more importantly, books published before 1985 make up a significant portion of the collections at many public and school libraries. Particularly in these tough economic times, they'd be unable to buy newer replacements for even those that had new copies available. Finally, older children's books were often more intellectually challenging than today's books; they used bigger vocabularies, more complex sentence structure, and overall more demanding texts. (I'll try to add sources for all these claims tomorrow - I'm ready for bed now.)

4 comments:

This is a lovely post. I love your point that the loss of these books, particularly in original printings with higher quality artwork, potentially hinders the develpment of modern and future artists.

It also occurs to me that many of the books that I've enjoyed over the last few years were books that had fallen out of favor and then decades later been republished. Henty, Ballentyne, Yonge, Appleton, the whole publishers list at houses like Bethleham Books or Purple House Press all fall into these categories. But if we destroy this broad swath of children's literature, where are our children and grandchildren going to find copies to rediscover?

I enjoyed reading this and especially agree that we need to keep inexpensive and free books available for children.

A few years ago, I bought a book (for $1 or less) that held a receipt for books purchased by Mrs. P. K. Wrigley (of Wrigley chewing gum) during the 1950's.

Of the several books that this very wealthy woman had purchased for her children, my children own a copy of every single one.

We're not wealthy. If I could only buy new books and used books post-1985, our library would be a small fraction of itself, not only in quantity but in literary quality as well.

After studying the childhoods of hundreds of men and women, Victor Goertzl wrote in Cradles of Eminence, "A rule of thumb for predicting future success is to know the number of books in the home."

To save face, Congress will hurt America's children.

Brilliantly said. Wow. I've added you to my blog feeds.

Kim in TX, Book binder and conservator, collector, homeschool mom, and mommy blogger.

Thanks everyone for your nice comments. It's so reassuring to see so many book lovers joining the fight - and I'm becoming more and more convinced it's going to be a knock-down, drag-out, no holds barred one. (Thank goodness I'm the mother of two wrestlers.)

Valerie, SO COOL about your Wrigley finds! Try to match that thrill with a new book. (Not that I'm dissing new books - as a still publishing author and illustrator I definitely want people to fall in love with the fresh-off-the-presses ones too.)

Post a Comment